The Hardy-Weinberg Principle in 2026: The Mathematical Compass of Population Genetics

In the era of 2026, where Personal Genomics and CRISPR-based gene therapies are household terms, we often get lost in the complexity of DNA sequences. We look at millions of base pairs, trying to find the one mutation that causes a disease or drives a species to evolve. Yet, amidst this high-tech biological revolution, the cornerstone of population genetics remains a mathematical theorem formulated over a century ago: the Hardy-Weinberg Principle.

While basic biology textbooks introduce this concept as a simple equation of $p^2 + 2pq + q^2 = 1$, for the modern researcher and the competitive exam aspirant (CSIR NET, GATE, NEET), it is much more. It is the “Null Hypothesis” of evolution—the baseline against which we measure change. Without the Hardy-Weinberg Principle, we could not calculate carrier risks for genetic diseases, we could not prove paternity in forensic science, and we could not manage the conservation of endangered species like the Great Indian Bustard.

In this extensive guide, we will move beyond the superficial definitions found in standard notes. We will explore the statistical depth of the principle, its application in 2026’s genomic medicine, and how to statistically prove deviation using the Chi-Square test—topics often skipped by competitors.

The “Null Hypothesis” of Evolution: Why Stasis Matters

To understand motion, you must first understand rest. In physics, Newton defined inertia. In biology, G.H. Hardy and Wilhelm Weinberg defined genetic inertia.

The Hardy-Weinberg Principle states that: “In a large, random-mating population, allele and genotype frequencies will remain constant from generation to generation in the absence of other evolutionary influences.”

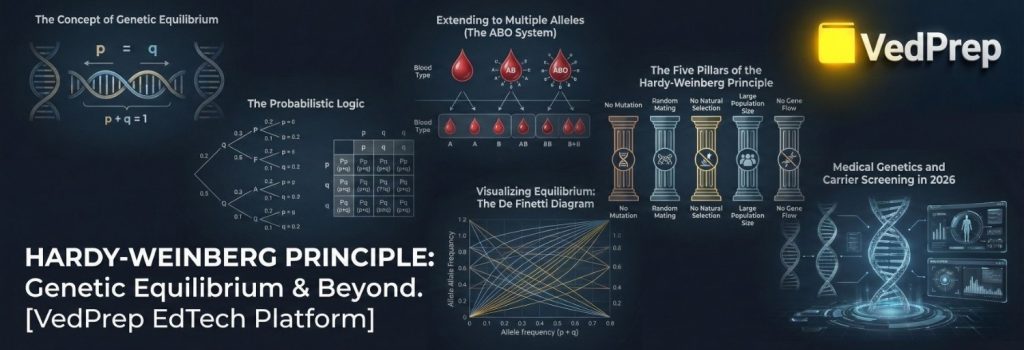

The Concept of Genetic Equilibrium

Imagine a population where nothing happens. No one moves in or out. No mutations occur. Everyone mates randomly, and everyone survives equally well. In this theoretical utopia, the gene pool remains frozen in time.

This state is called Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium.

Why is this important in 2026? Because nature is never in equilibrium. By comparing a real population to the Hardy-Weinberg Principle prediction, scientists can detect evolution in action. If the numbers don’t match, it means one of the evolutionary forces (Selection, Drift, Mutation) is at work. It acts as a biological alarm system.

The Mathematical Backbone: Beyond the Basic Equation

Most students memorize the formula but fail to understand the probability logic behind it. Let’s deconstruct the mathematics of the Hardy-Weinberg Principle.

The Probabilistic Logic

Consider a single gene locus with two alleles: Dominant ($A$) and Recessive ($a$).

- Let the frequency of allele $A$ be $p$.

- Let the frequency of allele $a$ be $q$.

- Since there are only two alleles, $p + q = 1$.

When this population mates, it is essentially a game of probability. You are picking two alleles from the gene pool to make an individual.

- Probability of being Homozygous Dominant (AA): You must pick an $A$ from the father ($p$) and an $A$ from the mother ($p$).

$$Probability = p \times p = p^2$$ - Probability of being Homozygous Recessive (aa): You must pick an $a$ from the father ($q$) and an $a$ from the mother ($q$).

$$Probability = q \times q = q^2$$ - Probability of being Heterozygous (Aa): There are two ways to do this. $A$ from dad and $a$ from mom ($pq$), OR $a$ from dad and $A$ from mom ($qp$).

$$Probability = pq + qp = 2pq$$

Thus, the genotype frequencies in the next generation are:

$$p^2 + 2pq + q^2 = 1$$

Extending to Multiple Alleles (The ABO System)

In 2026, we deal with complex traits. What if there are 3 alleles (like blood groups $I^A$, $I^B$, $i$)? The Hardy-Weinberg Principle expands elegantly using the multinomial expansion.

Let frequencies be $p, q, r$.

$$(p + q + r)^2 = 1$$

$$p^2 + q^2 + r^2 + 2pq + 2pr + 2qr = 1$$

This flexibility allows the principle to be applied to complex forensic DNA profiling involving Short Tandem Repeats (STRs) with dozens of alleles.

The Five Pillars of the Hardy-Weinberg Principle

The equilibrium holds true only if five specific conditions are met. In the real world, these conditions are constantly violated, which is what drives evolution.

1. No Mutation (The CRISPR Variable)

- The Condition: The gene pool must not change due to DNA errors.

- The Reality: Mutations are the raw material of evolution. In 2026, with the rise of gene editing technologies like CRISPR-Cas9, humans are actively introducing “artificial mutations” to cure diseases. This is a deliberate violation of the Hardy-Weinberg Principle to remove deleterious alleles from the human gene pool.

2. Random Mating (Panmixia)

- The Condition: Individuals must choose mates without regard to their genotype.

- The Reality: Mating is rarely random. Humans practice Assortative Mating (choosing partners with similar height, intelligence, or skin color). This increases Homozygosity ($p^2$ and $q^2$) and decreases Heterozygosity ($2pq$), deviating from the Hardy-Weinberg Principle predictions without necessarily changing allele frequencies.

3. No Gene Flow (Migration)

- The Condition: The population must be isolated.

- The Reality: In a globalized world, human populations are mixing at unprecedented rates. Migration introduces new alleles, homogenizing populations and breaking local Hardy-Weinberg Principle equilibriums.

4. Infinite Population Size (No Genetic Drift)

- The Condition: The population must be huge to prevent statistical sampling errors.

- The Reality: Endangered species (like the Snow Leopard) live in small, fragmented populations. Here, chance events (a fire killing the only fertile male) can eliminate alleles randomly. This is Genetic Drift. The Hardy-Weinberg Principle fails spectacularly in small populations, which is why conservationists strive to maintain a “Minimum Viable Population.”

5. No Natural Selection

- The Condition: All genotypes must have equal survival and reproductive success.

- The Reality: Some genes are better. The sickle cell allele ($HbS$) provides resistance to malaria. In malaria-prone regions, Heterozygotes ($HbA/HbS$) survive better than both Homozygotes. This “Heterozygote Advantage” maintains the allele frequencies in a balance that is distinct from a neutral Hardy-Weinberg Principle equilibrium.

Determining Deviation: The Chi-Square Test ($X^2$)

This is a critical topic for advanced students that most introductory blogs miss. How do you know if a population is actually in Hardy-Weinberg Principle equilibrium or if the difference is just random noise? You use statistics.

The Workflow:

- Observe: Count the actual number of genotypes in the population (Observed).

- Calculate Allele Frequencies: Determine $p$ and $q$ from the observed data.

- Predict: Use $p^2, 2pq, q^2$ to calculate the Expected number of individuals if the population were in equilibrium.

- Test: Use the Chi-Square formula:

$$\chi^2 = \sum \frac{(Observed – Expected)^2}{Expected}$$ - Conclude: If the calculated $\chi^2$ value is greater than the critical table value (usually 3.84 for 1 degree of freedom), the population is NOT in equilibrium. Evolution is happening.

This statistical rigor is what makes the Hardy-Weinberg Principle a scientific tool rather than just a theory.

Medical Genetics and Carrier Screening in 2026

The most life-saving application of the Hardy-Weinberg Principle is in calculating the risk of hidden genetic diseases.

The Carrier Equation

Many genetic disorders like Cystic Fibrosis, Thalassemia, and Phenylketonuria (PKU) are recessive. You only get the disease if you are $aa$ ($q^2$). However, the dangerous alleles hide in healthy carriers ($Aa$).

- If we know the incidence of a disease (e.g., 1 in 10,000 babies has PKU), we can calculate the carrier frequency.

- $q^2 = 1/10,000 = 0.0001$

- $q = \sqrt{0.0001} = 0.01$

- $p = 1 – 0.01 = 0.99$

- Carrier Frequency ($2pq$): $2 \times 0.99 \times 0.01 \approx 0.02$ (or 2%).

In 2026, genetic counselors will use the Hardy-Weinberg Principle daily to tell prospective parents the probability of their child inheriting a rare condition, even before expensive sequencing is done.

X-Linked Traits: The Gender Divide

The principle applies differently to sex chromosomes.

- Females ($XX$): Follow standard $p^2 + 2pq + q^2$.

- Males ($XY$): Since they have only one X, their genotype frequency equals the allele frequency.

- Frequency of Colorblind Males = $q$

- Frequency of Colorblind Females = $q^2$

This explains mathematically why X-linked diseases are so much more common in men. The Hardy-Weinberg Principle provides the exact ratio of this disparity.

Visualizing Equilibrium: The De Finetti Diagram

Advanced population genetics uses geometry to understand these frequencies. The De Finetti Diagram (often called the Ternary Plot) is a triangular coordinate system used to visualize the frequencies of three genotypes.

However, the simpler Hardy-Weinberg Parabola is more common in exams.

- X-Axis: Allele Frequency ($q$)

- Y-Axis: Genotype Frequency

- The Curve:

- $q^2$ (Homozygous Recessive) rises exponentially.

- $p^2$ (Homozygous Dominant) falls exponentially.

- $2pq$ (Heterozygotes) forms an inverted parabola (an arch).

Key Insight: The peak of Heterozygosity occurs exactly when allele frequencies are equal ($p = 0.5, q = 0.5$). At this point, 50% of the population are carriers. This graph is a favorite in CSIR NET questions to test understanding of the Hardy-Weinberg Principle.

Forensics and the “CSI Effect”

In 2026, crime solving relies heavily on DNA profiling. When a DNA sample from a crime scene matches a suspect, how do we know it’s not a coincidence?

We use the Hardy-Weinberg Principle.

Forensic scientists analyze 13-20 specific regions (loci) on the DNA. For each locus, they calculate the probability of that specific genotype occurring using $2pq$ or $p^2$. Then, they multiply the probabilities of all loci (Product Rule).

The result is often numbers like “1 in 1 quadrillion chance.” This statistical certainty, which puts criminals behind bars, is entirely derived from the Hardy-Weinberg Principle.

Common Misconceptions to Avoid

Even smart students fall into specific traps regarding this topic.

- Misconception: “Dominant alleles will eventually take over the population.”

- Fact: The Hardy-Weinberg Principle proves that allele frequencies do not change just because one is dominant. Dominance refers to the phenotype, not reproductive advantage. If $p=0.1$, it will stay $0.1$ forever unless selection acts on it.

- Misconception: “Heterozygotes are always 50%.”

- Fact: Heterozygotes ($2pq$) are 50% only when $p=0.5$. If an allele is rare ($q=0.01$), heterozygotes are rare (2%), but still much more common than homozygous recessives ($0.01\%$).

VedPrep: Decoupling the Math from the Biology

The Hardy-Weinberg Principle sits at the uncomfortable intersection of Biology and Mathematics. For many Life Science students preparing for exams like CSIR NET, GATE, or NEET, this is the “danger zone.” You might understand the biology of evolution, but if you mess up the calculation of $2pq$ or misinterpret a Chi-Square value, you lose critical marks.

This is where VedPrep steps in as your strategic advantage.

At VedPrep, we understand that you are training to be a biologist, not a statistician. Our specialized modules on Population Genetics are designed to demystify the numbers.

- The “No-Fear” Calculation Method: We teach structured, step-by-step protocols to solve Hardy-Weinberg Principle problems. Whether it’s calculating carrier frequencies for X-linked traits or adjusting for multiple alleles, our methods ensure you never get lost in the algebra.

- Visualizing Evolution: Instead of dry equations, we use dynamic graphs and simulations to show how Genetic Drift and Selection warp the Hardy-Weinberg parabola in real-time.

- Exam-Centric Case Studies: We analyze previous years’ questions from top exams to show you the “trick” questions—where the examiner tests your assumption of equilibrium rather than the math itself.

With VedPrep, the Hardy-Weinberg Principle transforms from a mathematical hurdle into your highest-scoring weapon. We bridge the gap between theory and application, ensuring you are ready not just for the exam, but for the research lab of 2026.

Conclusion

The Hardy-Weinberg Principle is a testament to the power of simplicity. With a basic binomial expansion, Hardy and Weinberg captured the essence of genetic stability. In the century since, we have discovered DNA, cracked the genetic code, and learned to rewrite genomes. Yet, this principle remains the unshakeable foundation.

In 2026, as we face challenges like preserving biodiversity in the face of climate change or screening populations for new genetic disorders, the Hardy-Weinberg Principle is more relevant than ever. It allows us to see the invisible forces of evolution at work. It helps us quantify the risk of disease. It provides the statistical proof needed for justice.

For the student, mastering this principle is not just about memorizing $p^2 + 2pq + q^2 = 1$. It is about understanding the delicate balance of life. It is about realizing that in the grand equation of nature, change is the only constant, but the Hardy-Weinberg Principle gives us the ruler to measure it.

Frequently asked questions (FAQs)

What is the Hardy-Weinberg Principle in simple terms?

Ans: The Hardy-Weinberg Principle acts as the "Null Hypothesis" of evolution. It states that in a large, randomly mating population, allele and genotype frequencies remain constant (frozen in time) unless specific evolutionary forces like mutation or selection act upon them.

Why is the Hardy-Weinberg Principle called the "Null Hypothesis" of evolution?

Ans: It serves as a baseline to measure change. By comparing a real population's data to the principle's predictions, scientists can determine if evolution is occurring. If the numbers don't match, it proves evolutionary forces are at work.

What is the basic equation for the Hardy-Weinberg Principle?

Ans: The fundamental equation is $p^2 + 2pq + q^2 = 1$, where $p^2$ represents the frequency of homozygous dominant individuals, $2pq$ represents heterozygotes, and $q^2$ represents homozygous recessive individuals.

How do I calculate carrier frequency if I know the disease incidence?

Ans: If you know the incidence of a recessive disease ($q^2$), first take the square root to find the allele frequency ($q$). Then, calculate the dominant allele frequency ($p = 1 - q$). Finally, use $2pq$ to find the carrier frequency.

How does the Hardy-Weinberg Principle handle multiple alleles, like the ABO blood group?

Ans: For three alleles ($p, q, r$), the equation expands using a multinomial expansion: $(p + q + r)^2 = 1$, which results in $p^2 + q^2 + r^2 + 2pq + 2pr + 2qr = 1$. This method is used for complex traits.

What is the Chi-Square test used for in population genetics?

Ans: The Chi-Square ($X^2$) test is a statistical tool used to determine if a population is significantly deviating from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium or if the difference is just random noise. It compares Observed values against Expected values.

How do X-linked traits differ in Hardy-Weinberg calculations?

Ans: For X-linked traits, males ($XY$) have only one X chromosome, so their genotype frequency equals the allele frequency (Frequency = $q$). Females ($XX$) follow the standard $p^2 + 2pq + q^2$ distribution. This explains why X-linked diseases are more common in males

What are the five conditions required for Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium?

Ans: The five pillars are: 1) No Mutation, 2) Random Mating (Panmixia), 3) No Gene Flow (Migration), 4) Infinite Population Size (No Genetic Drift), and 5) No Natural Selection.

How does Genetic Drift affect the Hardy-Weinberg prediction?

Ans: Genetic Drift occurs in small populations where chance events (like an accidental death) eliminate alleles randomly. This violates the "Infinite Population Size" condition, causing the principle to fail in predicting frequencies accurately.

What is the "Heterozygote Advantage" and how does it violate equilibrium?

Ans: This occurs when Heterozygotes (like $HbA/HbS$ in malaria regions) survive better than both homozygous genotypes. This form of Natural Selection maintains allele frequencies in a balance different from neutral equilibrium.