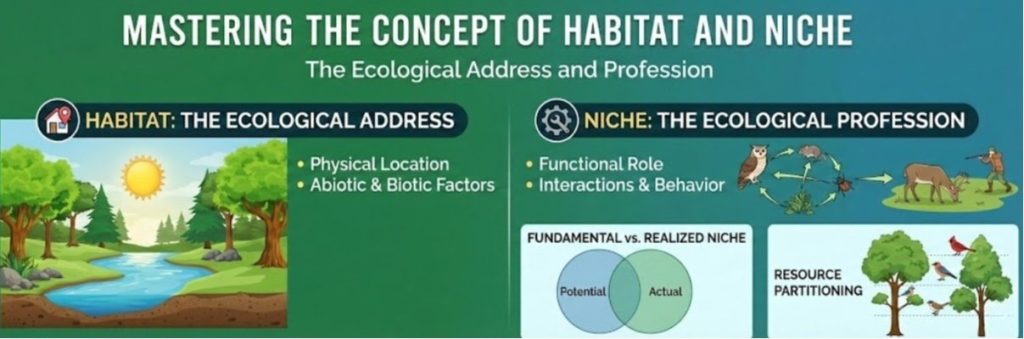

Mastering the Concept of Habitat and Niche: The Ecological Address and Profession

Ecology is the scientific study of interactions among organisms and between organisms and their environment. To truly understand these interactions, one must master two fundamental concepts: habitat and niche. While often used interchangeably in casual conversation, these terms hold distinct, critical meanings in the scientific world. Understanding the concept of habitat and niche is not just about passing an exam; it is about seeing the natural world as a structured, functioning system where every species has a specific address and a specific job.

This guide goes beyond simple definitions. We will explore the theoretical frameworks, the types of niches that drive evolution, and how these concepts apply to conservation biology today. Whether you are a CSIR NET aspirant or a biology enthusiast, this deep dive will clarify the “where” and “how” of life on Earth.

Decoding the Habitat: The “Address” of an Organism

A habitat is effectively the physical location where an organism lives. It is the “address” where you can find a specific species. However, a habitat is more than just a pin on a map; it is a complex amalgamation of physical and chemical factors that allow a species to survive, grow, and reproduce.

The Components of a Habitat

A habitat consists of both biotic (living) and abiotic (non-living) components. It is the interplay between these two that determines the quality of the “address.”

- Abiotic Factors: These are the non-living chemical and physical parts of the environment that affect living organisms and the functioning of ecosystems.

- Temperature: Determines the metabolic rates of organisms. Polar bears require sub-zero temperatures, while camels are adapted to scorching heat.

- Water: The universal solvent. Its availability, salinity, and pH dictate which species can survive.

- Light: Essential for photosynthesis in plants, which forms the base of the food web.

- Soil: The composition, pH, and texture of soil determine the vegetation, which in turn determines the herbivores present.

- Biotic Factors: These include all the living things that an organism interacts with.

- Food Availability: The presence of prey or plants is a defining characteristic of a habitat.

- Predators and Competitors: The presence of these biological pressures shapes how an organism uses its habitat.

Types of Habitats: From Micro to Macro

Habitats are not one-size-fits-all. They vary immensely in scale and complexity.

- Terrestrial Habitats: These are land-based environments. They are further classified based on climate and vegetation into biomes like forests, grasslands, deserts, and tundra.

- Aquatic Habitats: These cover water-based environments.

- Freshwater: Ponds, lakes, rivers, and streams.

- Marine: Oceans, coral reefs, and estuaries.

- Microhabitats: Within a larger habitat, there exist smaller, specialized areas. For example, in a forest habitat, a decaying log represents a microhabitat for fungi, beetles, and mosses. It has a different humidity, temperature, and light level compared to the forest canopy above it.

The Niche: The “Profession” of an Organism

If the habitat is the address, the niche is the profession. A niche encompasses not just where an organism lives, but how it lives. It includes the functional role the organism plays in the ecosystem—what it eats, who eats it, how it behaves, when it is active, and how it reproduces.

The Dimensions of a Niche

Ecologist G.E. Hutchinson formalized the concept of the niche as an “n-dimensional hypervolume.” This sounds complex, but it simply means that a niche is defined by multiple environmental factors (dimensions) that affect a species’ survival.

- Trophic Dimension: What does the organism eat? Is it a primary producer, a herbivore, or a top predator?

- Spatial Dimension: Where exactly does it operate? Does it forage in the tree canopy or on the forest floor?

- Temporal Dimension: When is it active? Is the species diurnal (active by day), nocturnal (active by night), or crepuscular (active at dawn/dusk)?

For example, two species of owls might live in the same forest habitat. However, one hunts mice at night, while the other hunts small birds during the day. Their spatial habitat overlaps, but their temporal niche is different, allowing them to coexist.

Fundamental vs. Realized Niche

A critical distinction in ecology is the difference between what an organism can do and what it actually does.

- Fundamental Niche: This is the theoretical range of environmental conditions and resources that a species can tolerate and use. It describes the potential life of the organism if there were no competition, predation, or limited resources. It is the “dream job” scenario.

- Realized Niche: This is the actual lifestyle the organism pursues in the real world. Because of competition from other species, predation risk, and resource limitations, a species often occupies a smaller subset of its fundamental niche. This is the “actual job” the organism performs.

Example:

Barnacles in the intertidal zone. One species (Chthamalus) can theoretically live in both deep and shallow water (Fundamental Niche). However, a larger, more aggressive species (Balanus) outcompetes it in the deep water. Therefore, Chthamalus is forced to live only in the shallow, high-tide zone (Realized Niche).

Habitat vs. Niche: The Critical Differences

Confusion between habitat and niche is common. Let’s break down the differences clearly.

| Feature | Habitat | Niche |

| Definition | The physical place where an organism lives. | The functional role an organism plays in that place. |

| Analogy | The “Address” (e.g., 221B Baker Street). | The “Profession” (e.g., Detective). |

| Specificity | Can be shared by many species. | Highly specific to a single species. |

| Components | Physical (abiotic) and biological (biotic) location. | Interactions, flow of energy, and behavior. |

| Change | A habitat changes slowly over geological time. | A niche can change quickly (e.g., due to competition). |

A habitat is a location; a niche is an interaction. A forest is a habitat for a tiger, a deer, and a tree. But the niche of the tiger is to control herbivore populations, while the niche of the deer is to graze and disperse seeds.

The Principle of Competitive Exclusion

The concept of the niche leads directly to one of the most famous rules in ecology: Gause’s Principle of Competitive Exclusion.

“Complete Competitors Cannot Coexist”

This principle states that two species competing for the exact same limiting resources cannot coexist at constant population values. If two species have an identical niche, one will have a slight advantage (more efficient at gathering food, faster reproduction) and will eventually drive the other to extinction in that local area.

Resource Partitioning: The Solution to Competition

Nature hates waste and extinction is costly. To avoid the dire consequences of competitive exclusion, species evolve to separate their niches. This is called Resource Partitioning.

- Spatial Partitioning: Different species of warblers (birds) might live in the same tree habitat, but one feeds on the outer branches, another on the inner branches, and a third on the trunk. They have partitioned the space to avoid niche overlap.

- Temporal Partitioning: As mentioned with owls, shifting activity times allows species to share the same resources without direct conflict.

- Dietary Partitioning: Finches on the Galapagos Islands evolved different beak sizes to eat different types of seeds. By specializing in different foods, they avoided competing for the same dietary niche.

Ecological Equivalents

Sometimes, you find different species in different parts of the world that look and act very similar. These are called Ecological Equivalents.

Ecological equivalents are species that occupy similar niches but live in different geographical regions. They are not necessarily related taxonomically, but they have evolved similar adaptations because they face similar environmental pressures in their respective habitats.

- Example: The Kangaroo in the grasslands of Australia and the Bison in the grasslands of North America. Both are large herbivores that graze on tough grasses. They live in a similar “Grassland Habitat” and occupy a similar “Grazer Niche,” yet they are completely different animals on different continents.

Why Understanding Habitat and Niche Matters for Conservation

In the modern world, the concepts of habitat and niche are not just academic theories; they are vital tools for conservationists fighting to save biodiversity.

Habitat Destruction vs. Niche Displacement

The biggest threat to wildlife today is habitat loss. When we cut down a rainforest, we are destroying the physical address of millions of species. Without a habitat, the organism has nowhere to exist.

However, niche displacement is equally dangerous but more subtle. Invasive species are a prime example. When a new species is introduced to an ecosystem (like the Water Hyacinth in Indian lakes), it often has no natural predators. It aggressively expands its niche, stealing resources from native species. The native species still have their habitat (the water is still there), but their niche (access to sunlight and nutrients) has been stolen. Understanding this helps rangers and scientists manage invasive species effectively.

Niche Construction Theory

Organisms don’t just passively live in a habitat; they change it. This is called Niche Construction.

- Beavers: They build dams, creating a pond habitat where there was once a stream. This new habitat supports fish, ducks, and amphibians that couldn’t live there before.

- Earthworms: By burrowing, they aerate the soil, changing its chemistry and structure. They literally build a better habitat for themselves and for plant roots.

Recognizing that species are “ecosystem engineers” helps us understand that conserving one species (like the beaver) can save an entire habitat for hundreds of others.

VedPrep: Defining Your Niche in CSIR NET Preparation

In the competitive ecosystem of the CSIR NET Life Sciences exam, Gause’s “Competitive Exclusion Principle” applies to students just as much as it does to wild animals. Thousands of aspirants compete for a limited resource—the JRF Fellowship. If you try to occupy the same “Generalist Niche” as everyone else—attempting to cover 100% of the syllabus superficially—you risk being outcompeted.

To secure your seat, you need to define your Realized Niche. You must transition from a passive student to an active strategist. This is where VedPrep becomes your essential habitat.

- Your Habitat for Success: Just as an organism needs specific abiotic factors to thrive, you need the right resources. VedPrep provides a curated ecosystem of high-quality video lectures, concise notes, and “Comparative Flashcards” that act as the perfect environment for your preparation.

- Strategic Resource Partitioning: Our philosophy of “Strategic Depth over Superficial Width” helps you partition your time effectively. Instead of grazing on low-yield topics, we guide you to hunt down the high-weightage units (like Ecology, Evolution, and Cell Bio) that guarantee marks.

- Evolutionary Advantage: With our specialized “Logic Training” for Part C questions, we help you evolve the analytical skills necessary to survive the toughest questions the examiner throws at you.

Don’t let the competition drive you to extinction. Adapt, specialize, and dominate your niche with VedPrep.

Conclusion

The concepts of habitat and niche are the yin and yang of ecology. The habitat provides the stage—the physical context of soil, water, and air. The niche provides the script—the active roles of eating, competing, and reproducing that drive the drama of life.

From the microscopic battle for dominance in a drop of water to the grand migration of wildebeest across the savannah, every biological event is governed by these rules. As we face a changing climate, understanding the flexibility of a species’ niche and the resilience of its habitat will be the key to predicting which species will survive the next century.

For students of life sciences, mastering the distinction between habitat and niche is the first step toward understanding the complex, beautiful, and fragile web of life on Earth.

Frequently Asked questions (FAQs)

What is the fundamental difference between a habitat and a niche?

Ans: A habitat is the physical "address" or location where an organism lives, while a niche is its "profession" or functional role within that ecosystem, including how it interacts, eats, and behaves.

Can multiple species share the same habitat?

Ans: Yes, a habitat can be shared by many different species (e.g., a forest is home to tigers, deer, and trees), whereas a niche is highly specific to a single species.

What are the two main components that make up a habitat?

Ans: A habitat consists of abiotic factors (non-living chemical and physical parts) and biotic factors (living organisms).

What are some examples of abiotic factors in a habitat?

Ans: Examples include temperature, water availability/quality, light intensity for photosynthesis, and soil composition .

What defines a "microhabitat"?

Ans: A microhabitat is a smaller, specialized area within a larger habitat that has different conditions (humidity, light, etc.), such as a decaying log on a forest floor .

What are the three main dimensions of a niche?

Ans: They are the Trophic Dimension (what it eats), Spatial Dimension (where it operates), and Temporal Dimension (when it is active) .

What is the difference between a Fundamental Niche and a Realized Niche?

Ans: A Fundamental Niche is the theoretical, potential range of resources an organism can use without competition. A Realized Niche is the actual lifestyle it pursues due to limitations like competition and predation .

Can you give an example of a Realized Niche?

Ans: A classic example is the barnacle Chthamalus, which can theoretically live in deep water (Fundamental) but is forced into the shallow high-tide zone (Realized) because the aggressive barnacle Balanus outcompetes it in deeper waters .

Does a niche remain constant?

Ans: No, unlike a habitat which changes slowly over geological time, a niche can change quickly due to factors like competition or new environmental pressures.

What is Gause’s "Principle of Competitive Exclusion"?

Ans: This principle states that "Complete Competitors Cannot Coexist." If two species compete for the exact same limited resources (identical niche), one will eventually drive the other to extinction .

How do species avoid extinction when competing for resources?

Ans: They use Resource Partitioning, which involves evolving to use different parts of a resource (spatial), becoming active at different times (temporal), or eating different foods (dietary) to separate their niches .

What is an example of Spatial Partitioning?

Ans: Different species of warblers living in the same tree but feeding on different parts (outer branches vs. inner branches vs. trunk) to avoid niche overlap .

What are "Ecological Equivalents"?

Ans: These are species that live in different geographical regions (and are often unrelated) but occupy similar niches because they face similar environmental pressures

Can you provide an example of Ecological Equivalents?

Ans: The Kangaroo in Australia and the Bison in North America are ecological equivalents; both are large herbivores grazing on grasslands in different continents .

How does "Niche Displacement" differ from habitat destruction?

Ans: Habitat destruction removes the physical location (address), whereas niche displacement (often by invasive species) steals the resources and role of a native species while the physical habitat remains intact