Fundamental Principles of the Kinetic Theory of Gas

The Kinetic Theory of Gas is a theoretical framework explaining the macroscopic properties of gases, such as pressure and temperature, based on the microscopic motion of submicroscopic particles. It assumes that gas molecules are in constant, random motion, and that the average kinetic energy of these particles is directly proportional to the absolute temperature of the Gaseous State.

Foundations of the Kinetic Molecular Model of a Gas

The Kinetic molecular model of a gas describes matter in the Gaseous State as a collection of point-like particles that are far apart and move independently. This model serves as the structural basis for the Kinetic Theory of Gas, allowing scientists to calculate how individual molecular collisions translate into measurable physical forces like pressure within a container.

According to the Kinetic molecular model of a gas, the volume occupied by the gas molecules themselves is negligible compared to the total volume of the container. This vast empty space explains why substances in the Gaseous State are highly compressible. The model further posits that intermolecular forces of attraction or repulsion are non-existent in an ideal scenario, allowing particles to travel in straight lines until a collision occurs.

In this Kinetic molecular model of a gas, every collision is perfectly elastic. This means there is no net loss of kinetic energy during impacts between molecules or with the container walls. By viewing the Gaseous State through this lens, the Kinetic Theory of Gas provides a bridge between the Newtonian mechanics of individual atoms and the thermodynamic behavior of bulk matter.

Core Postulates of the Kinetic Theory of Gas

The Kinetic Theory of Gas relies on several key assumptions to simplify the complex behavior of molecules. These postulates state that gases consist of large numbers of identical particles in constant motion, and that the pressure exerted by a gas results from the frequent bombardment of container walls by these rapidly moving particles.

One primary postulate of the Kinetic Theory of Gas is that the actual volume of gas molecules is so small that it can be ignored. In the Gaseous State, the distance between molecules is significantly larger than the size of the molecules themselves. This assumption is a cornerstone of the Kinetic molecular model of a gas, enabling the derivation of the Ideal Gas Law (PV=nRT).

Another essential element of the Kinetic Theory of Gas is the relationship between heat and motion. The theory explicitly states that the average kinetic energy of gas particles is determined solely by the absolute temperature. As temperature increases, the speed of molecules in the Gaseous State increases, leading to more forceful and frequent collisions. This specific energy-temperature link is what defines the thermal properties of the Kinetic molecular model of a gas.

Understanding Pressure and Temperature in the Gaseous State

In the Gaseous State, pressure is defined as the average force per unit area exerted by gas molecules hitting the walls of their container. The Kinetic Theory of Gas explains that this pressure depends on the number of molecules present, their mass, and how fast they are moving at a given temperature.

Temperature is not just a measure of “hotness” but a reflection of molecular activity. The Kinetic Theory of Gas teaches us that temperature is the macroscopic manifestation of microscopic kinetic energy. When you heat a substance in the Gaseous State, you are directly adding energy to the Kinetic molecular model of a gas, causing the particles to zip around with greater velocity.

If the volume of a container is reduced while the temperature remains constant, the Kinetic Theory of Gas predicts that pressure will rise. This happens because the particles in the Gaseous State have less room to move, resulting in more frequent strikes against the walls. This clear cause-and-effect relationship between motion and force is the primary triumph of the Kinetic molecular model of a gas.

Distribution of Molecular Velocities

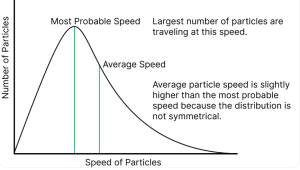

While the Kinetic Theory of Gas relates temperature to average kinetic energy, not all molecules in a Gaseous State move at the same speed. The Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution describes how speeds are spread across the population of particles within the Kinetic molecular model of a gas at a specific temperature.

At any given moment in a Gaseous State, some molecules move very slowly while others move extremely fast. The Kinetic Theory of Gas uses statistical methods to show that as temperature rises, the entire distribution shifts toward higher speeds. The peak of this distribution curve represents the most probable speed of a particle in the Kinetic molecular model of a gas.

This variation in speed is vital for chemical reactions. Only the high-energy “tail” of the distribution in the Gaseous State possesses enough energy to overcome activation barriers. By applying the Kinetic Theory of Gas, researchers can calculate the fraction of molecules that are “reactive” at a certain temperature, demonstrating the practical utility of the Kinetic molecular model of a gas in kinetics and thermodynamics.

Real Gas Deviations and the Van der Waals Correction

The Kinetic Theory of Gas primarily describes “Ideal Gases,” but real-world substances in the Gaseous State often deviate from these predictions at high pressure or low temperature. These deviations occur because real molecules do have finite volumes and experience weak intermolecular attractions.

When a gas is highly compressed, the assumption in the Kinetic molecular model of a gas that molecular volume is negligible becomes invalid. The particles are forced so close together that their own physical size takes up a significant portion of the total space. In these conditions, the Kinetic Theory of Gas must be adjusted using the Van der Waals equation to account for the “excluded volume” of the Gaseous State.

Intermolecular forces also play a role. In a standard Kinetic molecular model of a gas, we assume particles don’t stick together. However, at low temperatures, the slow-moving molecules in the Gaseous State begin to feel attractive forces. This reduces the force of their impact against container walls, leading to a lower pressure than the Kinetic Theory of Gas would otherwise predict for an ideal system.

Molecular Effusion and Diffusion Processes

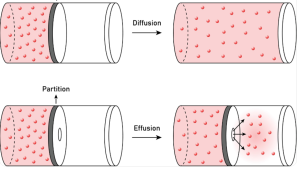

Diffusion is the gradual mixing of different gases due to random molecular motion, while effusion is the process of gas escaping through a tiny hole. The Kinetic Theory of Gas provides the mathematical basis for Graham’s Law, which relates these rates to the mass of the particles.

According to the Kinetic Theory of Gas, lighter molecules move faster than heavier ones at the same temperature. Consequently, a light gas in the Gaseous State, like Hydrogen, will diffuse much more rapidly than a heavy gas like Oxygen. This is a direct consequence of the Kinetic molecular model of a gas, where kinetic energy equality (1/2 mv²) dictates that lower mass (m) requires higher velocity (v).

Effusion is practically used in isotope separation and gas leak detection. By understanding the Kinetic molecular model of a gas, engineers can predict how quickly a specific Gaseous State mixture will pass through a membrane. The Kinetic Theory of Gas remains the essential tool for calculating these transport properties in both industrial and natural environments.

Critical Perspective: The Limit of the Point-Mass Assumption

A common belief in introductory physics is that the Kinetic Theory of Gas is universally applicable as long as the substance remains in the Gaseous State. However, this perspective fails to account for the “internal degrees of freedom” in complex molecules. The standard Kinetic molecular model of a gas often treats particles as simple point masses (monatomic), which works well for Helium or Neon.

When applying the Kinetic Theory of Gas to polyatomic gases like Carbon Dioxide or Water Vapor, the simple model fails to predict the correct heat capacity. This is because these molecules can rotate and vibrate, storing energy in ways the basic Kinetic molecular model of a gas does not track. To mitigate this limitation, the “Equipartition Theorem” must be integrated into the Kinetic Theory of Gas to account for these extra energy reservoirs in the Gaseous State. Without this adjustment, calculations regarding energy transfer in atmospheric or industrial chemistry would be significantly inaccurate.

Practical Application: Gas Pressure in Scuba Diving

The Kinetic Theory of Gas has life-saving applications in scuba diving, where changes in pressure directly affect the behavior of the Gaseous State within a diver’s lungs and blood. Understanding the Kinetic molecular model of a gas is essential for calculating safe ascent rates and preventing decompression sickness.

As a diver descends, the external water pressure increases. To keep the lungs inflated, the air must be delivered at a matching high pressure. Based on the Kinetic Theory of Gas, this means more molecules are packed into the same volume, increasing the density of the Gaseous State. This high-density environment changes the way the Kinetic molecular model of a gas interacts with the diver’s physiology.

-

Scenario: A diver at 30 meters depth.

-

Constraint: The partial pressure of Nitrogen increases according to the Kinetic Theory of Gas.

-

Outcome: Nitrogen molecules are forced into the blood at a higher rate.

-

Safety Step: A slow ascent allows the Gaseous State to gradually exit the blood. If the diver rises too fast, the Kinetic molecular model of a gas predicts that Nitrogen will form bubbles, much like opening a carbonated drink.

Mean Free Path and Collision Frequency

The mean free path is the average distance a molecule travels in the Gaseous State between successive collisions. The Kinetic Theory of Gas uses this concept to explain thermal conductivity and viscosity, as these properties depend on how effectively energy and momentum are “carried” through the Kinetic molecular model of a gas.

In a dense Gaseous State, the mean free path is very short because the particles are constantly bumping into each other. Conversely, in the high vacuum of outer space, the Kinetic molecular model of a gas would show molecules traveling kilometers before hitting another particle. The Kinetic Theory of Gas defines the mean free path as being inversely proportional to the pressure and the square of the molecular diameter.

Collision frequency, another vital metric from the Kinetic Theory of Gas, determines the rate of chemical reactions. For a reaction to occur in the Gaseous State, molecules must collide with sufficient energy and correct orientation. By analyzing the Kinetic molecular model of a gas, chemists can predict how increasing the concentration or temperature will boost the collision frequency, thereby accelerating the reaction.

The Concept of Root Mean Square (RMS) Speed

Since molecules in the Gaseous State move at varying velocities, the Kinetic Theory of Gas utilizes the Root Mean Square (RMS) speed as a statistically significant average. This value represents the speed of a molecule possessing the average kinetic energy of the entire Kinetic molecular model of a gas.

The formula for RMS speed, derived from the Kinetic Theory of Gas, is vrms=3RT/M. This equation shows that the average speed in a Gaseous State is directly proportional to the square root of the temperature (T) and inversely proportional to the square root of the molar mass (M). This explains why even at room temperature, light molecules in the Kinetic molecular model of a gas are moving at speeds exceeding hundreds of meters per second.

RMS speed is a more accurate representation for thermodynamic calculations than a simple arithmetic average. In the Kinetic Theory of Gas, the energy of the system is related to the square of the velocity. Therefore, the RMS value correctly captures the energetic profile of the Gaseous State, making it a fundamental variable in the study of the Kinetic molecular model of a gas.

Kinetic Energy and the Constant of Proportionality

The relationship between kinetic energy and temperature in the Kinetic Theory of Gas is bridged by the Boltzmann constant (kB). This constant allows us to calculate the energy of a single molecule in the Gaseous State, further refining the precision of the Kinetic molecular model of a gas.

For a single molecule, the average kinetic energy is given by (3/2)kBT. This elegant result from the Kinetic Theory of Gas demonstrates that at a given temperature, all gas molecules, regardless of their identity, have the same average kinetic energy. Whether it is a massive Xenon atom or a tiny Hydrogen molecule in the Gaseous State, their thermal energy is identical.

This principle is fundamental to the Kinetic molecular model of a gas because it implies that mass only affects the speed, not the energy. The Kinetic Theory of Gas thus provides a universal scale for thermal energy that applies to any substance in the Gaseous State, provided it behaves ideally. This universality is what makes the Kinetic molecular model of a gas such a powerful tool in physics and chemistry.

Summary of the Gaseous State Behavior

To master the Kinetic Theory of Gas, one must internalize the dynamic nature of the Gaseous State. The Kinetic molecular model of a gas is not a static picture but a description of a chaotic, high-energy system where billions of events occur every microsecond.

By studying the Kinetic Theory of Gas, we gain the ability to:

-

Predict how pressure changes with volume and temperature.

-

Understand the limits of the Gaseous State in extreme environments.

-

Visualize the invisible interactions within the Kinetic molecular model of a gas.

-

Calculate the speeds and energies of particles that make up our atmosphere.

The Kinetic Theory of Gas remains a cornerstone of modern science, providing the necessary framework for everything from weather forecasting to the design of jet engines. Understanding the Kinetic molecular model of a gas is the first step in appreciating the complex physics of the world around us.

For further information refer to the study material and visit the official Website.

| Related Link |

| IP University CUET PG 2026 |